Tokyo runs on one principle: consideration for shared space. Learn that, and the rest makes sense.

Tokyo culture and practicalities come down to one principle: consideration for shared space. Learn that, and the rest makes sense.

Most Japan guides list 30 etiquette rules to help you avoid offending locals. The reality: Japanese people are remarkably forgiving of tourist mistakes. What shapes your daily experience is understanding how things work, not memorizing what not to do.

You're Probably Worrying About the Wrong Things

What etiquette guides overemphasize

Pre-trip reading fixates on formalities that rarely affect tourists: business card protocols, precise bowing angles, chopstick rules, formal speech patterns. These fill articles because they're culturally interesting—not because they'll shape your trip.

Japanese people are patient with foreign visitors. They're so polite they would never say anything about minor mistakes. The etiquette perfection anxiety is unfounded.

What actually causes daily friction

The things that trip up visitors aren't cultural faux pas—they're practical systems. How do you order at this restaurant? Why won't this machine work? Where do you put your trash when there are no bins? Which of Shinjuku's 200 exits do you need?

These questions come up daily. Bowing angles don't.

The rest of this guide covers the systems that matter—and the short list of etiquette that affects your experience.

One Principle That Explains Everything

Consideration for shared space

Nearly every Japanese cultural norm traces back to one idea: don't cause inconvenience to others in shared spaces.

The Japanese call this meiwaku o kakenai (迷惑をかけない)—literally, "don't impose burden on others." Once you internalize this, unfamiliar situations become navigable.

How this shows up daily

-

Train quietness — Talking disturbs others trying to rest or focus

-

Queuing — Cutting in line affects everyone behind you

-

Carrying trash — Leaving garbage makes public spaces worse for others

-

Not eating while walking — Crumbs and spills affect shared sidewalks

-

Removing shoes indoors — Keeps interior floors clean for everyone

When you're unsure what to do, watch what locals do. Observation beats memorization. If your action would make the space worse for someone else, it's the wrong call.

The Systems That Actually Shape Your Day

Restaurants: Ordering systems vary by format

Tokyo restaurants use different systems depending on format:

Ticket machine restaurants (ramen, curry, soba, gyudon chains like Matsuya and Yoshinoya):

-

Insert cash first—buttons don't activate until you do

-

Press buttons for your order (top-left button is usually the most popular item)

-

Take ticket and change

-

Hand ticket to staff at your seat

At places like Ichiran, you'll also fill out a customization sheet for noodle firmness, spice level, and garlic—English versions are available at most locations. Popular ramen shops can have 30-60 minute waits at lunch (12:00-13:00); less famous spots or standing soba chains like Nadai Fuji Soba (¥250-500, served in under two minutes) skip the line entirely.

Counter restaurants: Many smaller restaurants seat 10-12 people at a counter. The chef prepares and serves directly. Finishing your food matters here—leaving large portions is considered wasteful. Solo dining is normal in Japan; counter seating is designed for it. Chains like Ichiran even have private booths with form-based ordering.

Full-service restaurants: Standard ordering from menus. English menus are common in Shibuya, Shinjuku, and Asakusa; rare in neighborhood spots. If navigating restaurant systems sounds like friction you'd rather skip, food tours handle the ordering and menu interpretation.

Payments: Where cash is still required

Card acceptance has increased significantly since COVID-19, but cash remains essential for:

-

Temple and shrine entrance fees

-

Standing bars—the izakayas under the tracks in Yurakucho (Gado-shita district) are almost entirely cash-only

-

Small neighborhood izakayas and restaurants

-

Street food vendors and food stalls

-

Festival vendors

-

Some vending machines

Hotels, department stores, major chains, and restaurants charging ¥1,000+ accept cards. Carry at least ¥5,000 cash per person per day. 7-Eleven ATMs at airports and throughout the city accept international cards.

What Etiquette Actually Matters

The five things that genuinely matter

Focus here:

-

Stay quiet on trains — No phone calls. Keep conversations low. Morning rush hours are silent.

-

Queue properly — Lines form everywhere: train doors, escalators, restaurants. Never cut.

-

Don't eat while walking — Finish food where you bought it, or find a bench. Convenience stores have eating areas for this reason.

-

Carry your trash — Public bins are scarce (the #1 complaint from foreign tourists in Japan's 2024 tourism survey). Pocket wrappers until you reach a convenience store (bins near entrance), JR station (bins near restrooms), or vending machine (bottle/can recycling attached). A small plastic bag in your daypack helps.

-

Remove shoes when indicated — Changing rooms, some restaurants, traditional accommodations, temple interiors. Look for a shoe area or follow others.

The common thread: these affect shared spaces or other people directly.

What you can safely ignore

As a tourist, don't worry about:

-

Business card protocols — Exchange rituals matter for business; you won't encounter them sightseeing

-

Bowing angles and duration — A slight head nod shows appreciation; nobody expects precise 30-degree bows

-

Complex chopstick rules — Don't point with them, don't pass food chopstick-to-chopstick (funeral custom), otherwise you're fine

-

Mastering indirect communication — Directness is fine when you're clearly a visitor

Effort matters more than perfection. Attempting to follow local customs is noticed and appreciated, even when imperfect.

Adjustment Happens in Waves, Not All at Once

Days 1-2: Everything works better than expected

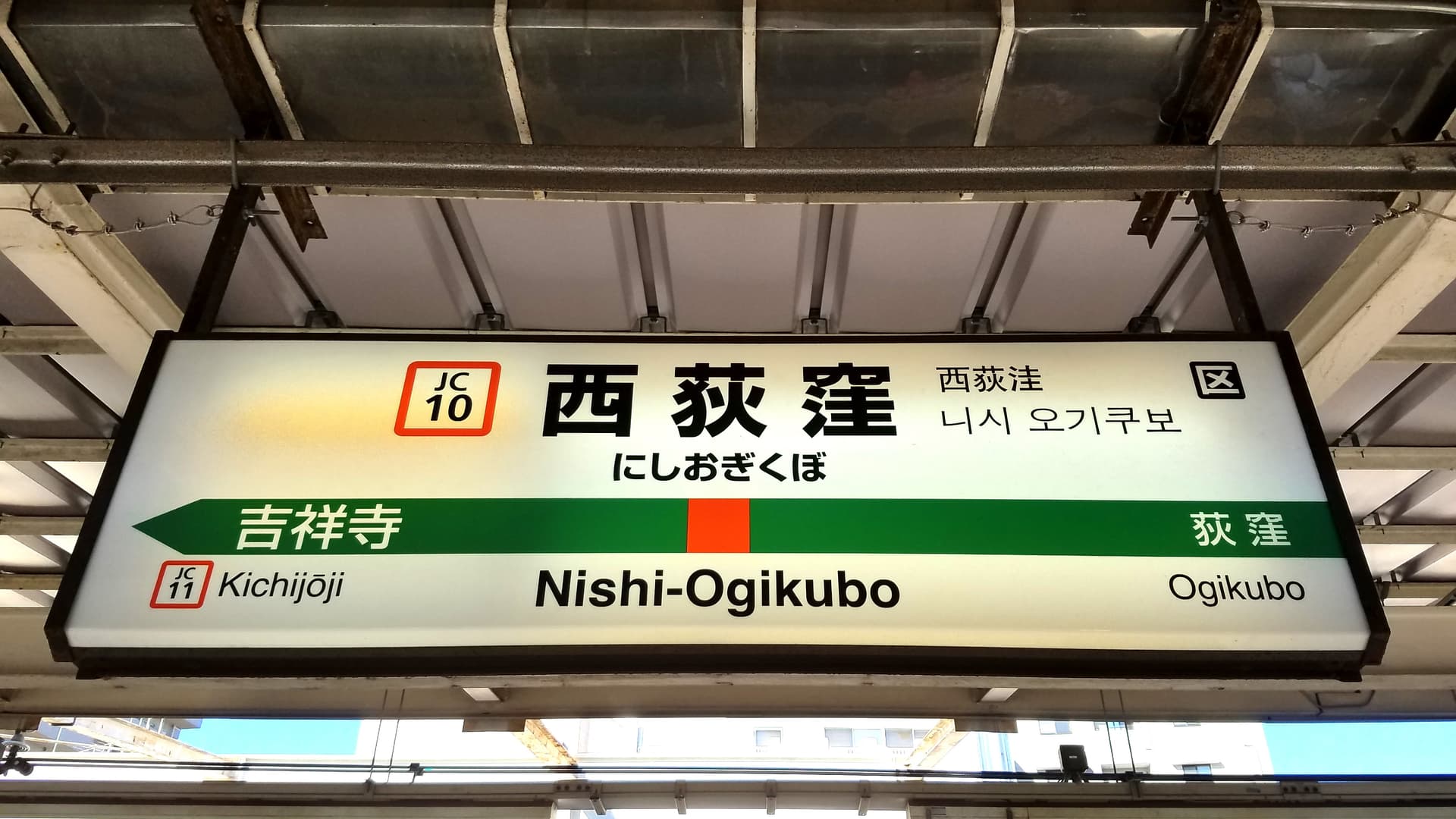

First-time visitors report the same surprise: Tokyo is easier to navigate than they feared. English signage at stations is comprehensive. Google Maps routing works. People are helpful when approached. The pre-trip anxiety fades quickly.

One timing note: most shops open at 10-11 AM, and many restaurants close between lunch (ending around 2 PM) and dinner (starting 5-6 PM). Early mornings are for temples, parks, and convenience stores.

This is normal. Enjoy the novelty and don't over-schedule.

Days 3-4: Decision fatigue sets in

Around day three or four, the constant low-level decision-making accumulates. Which exit? What's on this menu? How does this work? Small choices require more cognitive effort than at home. Active sightseeing days hit 15,000-20,000 steps—your feet notice.

This isn't failure—it's the middle of the adjustment curve. Schedule lighter days. Return to familiar areas. Use convenience stores for simple meals.

Day 5+: Systems start clicking

By the end of the first week, most visitors report a shift. The metro makes sense. Restaurant formats feel familiar. You start recognizing patterns. The city feels navigable rather than overwhelming.

This timeline holds for most travelers. The phrase we hear repeatedly: "I wish I'd known how easy and straightforward it would be."

Going Deeper

Safety and practical logistics

Tokyo is exceptionally safe, but practical questions remain—late-night transportation, what to do if you lose something, how safe specific areas are at night. Our guide to safety in Tokyo covers what visitors need to know.

Language and communication

The language barrier is real but manageable. Navigation works fine with apps; deeper interactions hit walls. Our guide to the language barrier explains what to expect and how to prepare. If you want cultural access beyond what apps provide, a private guide helps bridge that gap.

Cultural norms in detail

Tipping, gift-giving, and specific etiquette situations deserve more depth than a hub page provides. Our guide to tipping in Tokyo covers the rare exceptions where tips are appropriate.

This guide is published by Hinomaru One, a Tokyo-based private tour operator.